Why I Teach Writing

The first time I taught writing, more than a decade ago, I was terrified. I had no idea what I was doing. I knew I could write, yes, but could I teach writing? Did I have anything of value to convey? And, for that matter, can writing be taught at all, or is it a talent you are simply born with?

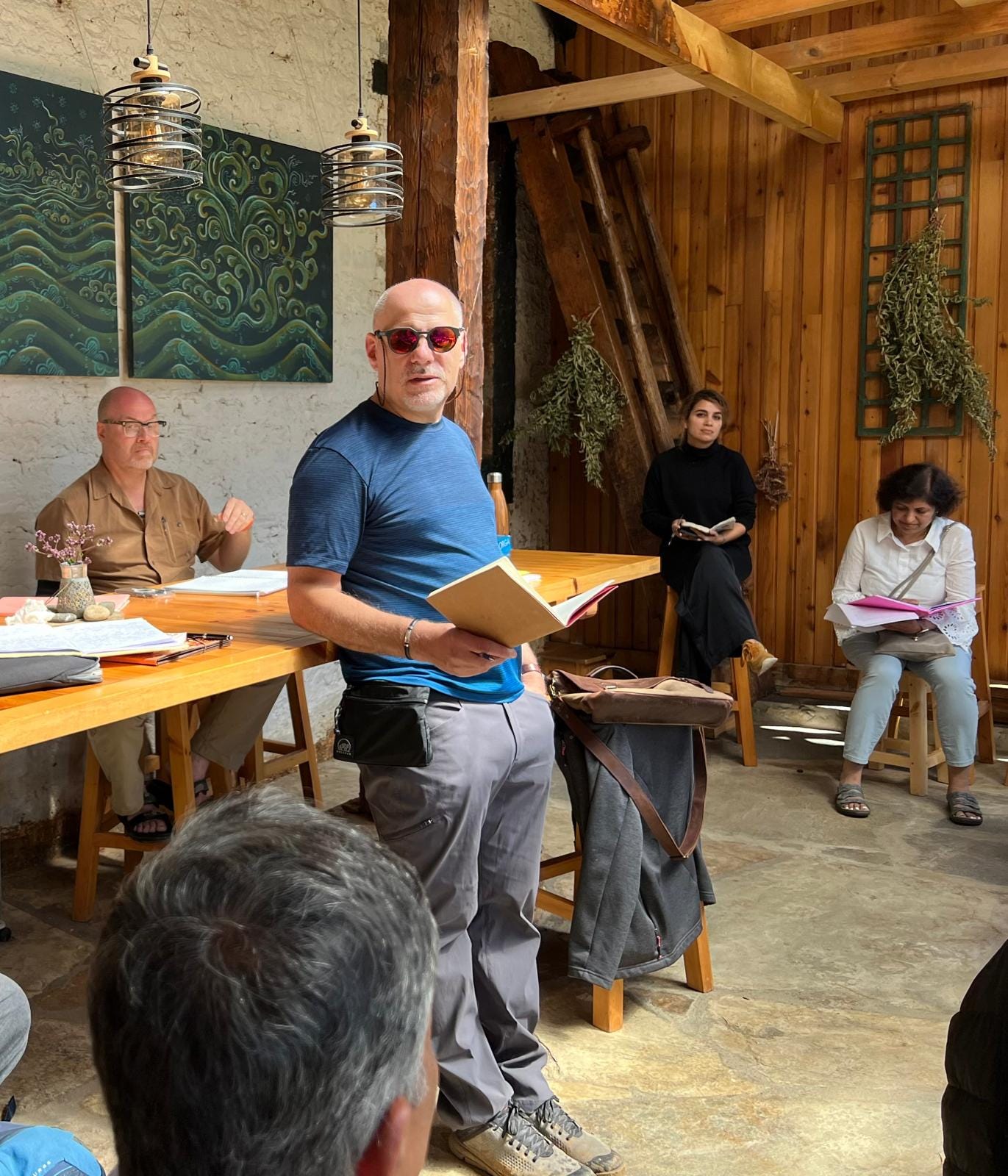

Of course, I didn’t disclose any of these doubts to my students, a dozen or so eager scribes gathered at a Kathmandu hotel for one of the inaugural sessions of the Himalayan Writers Workshop. They didn’t need to know I was winging it.

After a few minutes, though, a thought occurred that put me at ease. All writers are winging it. Always. We are not engineers, methodically adhering to construction codes and zoning regulations. We grope in the dark, unsure of both our routing and our destination, with no rulebook to follow. Yet we keep moving forward anyway. “Writing is like driving a car at night,” said the novelist E.L. Doctorow. “You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.”

It turns out that this few-feet-at-a-time method is true for teaching writing as well. There is no canon to convey, no methodology to impart. My role is less professor and more soccer coach, and mentor. Just another driver in the dark, albeit one who has logged a few more miles.

My main task is encouraging my students to trust their instincts, to get out of their own way. Kill your internal editor, I tell them. (Make it look like an accident.) Or I relay a piece of advice that has stuck with me for years: Don’t try to write well; write honestly.

Advice like this takes time to sink in. Fear of writing is second only to fear of math. I realized this when I taught a group of medical doctors. These were highly accomplished people at the top of their profession. They had undergone years of training and passed grueling board exams. They regularly held people’s lives in their hands. Yet the prospect of writing a personal essay terrified them.

Confidence in one field doesn’t necessarily translate to another. The dispassionate expertise demanded by the medical profession interfered with their ability to open up on the page. My task was to give them the confidence, the permission, to take that chance and play the role not of the all-knowing doctor but, rather, of the vulnerable patient. All writing worth reading springs from our most vulnerable places.

Learning to write is, in large part, unlearning bad habits and demolishing harmful myths. Among them are the belief that:

You can only write about what you know. Not true. The best writers write about what they want to know.

Good writing means using a lot of big words and complex sentences. Wrong. Good writing expresses even complex ideas simply and with taut, muscular language.

Writing is supposed to be easy. Real writers produce polished first drafts. False. “Real” writers produce messy, crappy first drafts and revise the heck out of them.

That is why I begin my workshops with Thomas Mann’s definition of a writer: “A writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.”I can hear the sighs of relief in the room. So, writing is not supposed to be easy? Exactly. In fact, if it’s not difficult you’re not doing it right. So, go ahead, feel free to write complete and utter crap. We will clean it up later. Together.

You’ve probably heard this cynical saying: “Those who can do; those who can’t, teach.” It is profoundly untrue. A more accurate rendition is, “Those who teach, do what they do better.” Teaching writing has made me a better writer. It has forced me to articulate and refine an assortment of inchoate principles and guidelines. It has forced me to give my students the confidence I don’t always give myself. And it has reaffirmed my conviction to a craft that is now my life’s calling.

I invite you to join me on one of my upcoming writing workshops next year: in Chiang Mai, Thailand and in Bhutan. Feel free to reply to this email with any questions.

We will be excited to see you in Bhutan.

A little add: So many Writers and public speakers, including seasoned pros feel they have to become Shakespearean in a public setting, and get the reverse result, sounding like the pedantry of a first-grade teacher.